What is the 3-Cueing Approach, and Why Is It Getting Banned?

Significant educational shifts are happening as states move toward aligning instruction to the science of reading, the vast, interdisciplinary body of scientifically-based research regarding reading, writing, and learning. Many are implementing laws and policies related to evidence-based reading instruction to bring change to classrooms. Since 2013, 29 states and the District of Columbia have passed laws or implemented new policies related to reading instruction. Recently, in Texas, legislation was put forth by House Bill 2162, which proposed banning the use of the three-cueing model in reading instruction. While Texas is not the first state to do so, it most likely won't be the last. What does this mean for teaching reading, and does it matter?

Why the Shift?

The current state of reading scores nationwide has raised questions about reading instruction and set a wave of change in motion. Emily Hanford's article Hard Words, podcasts, and those in the education field that have called for change for decades are starting to see more educators and parents reach out in hopes of better understanding the research and how it impacts reading instruction. The National Reading Panel was published in 2000 and outlined the necessary elements for reading instruction (phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension). However, this knowledge and implementation only made its way into some of the curriculums used in our classrooms, and many of the ineffective methods and models remained in the curriculums. One of these is the three-cueing model.

What is the 3-Cueing Model?

The three-cueing model is an approach based on the psycholinguistic theories of Ken Goodman & Frank Smith, first published in the 1960s, theorizing that readers rely on print as little as possible when reading and instead use language cues. This model prompts readers to use three cues to figure out unfamiliar words. Students are taught and encouraged that meaning should be the first focus and given cues with prompts such as "What makes sense?" and "Can you think of another word that would work in this sentence?" which focus on language and meaning. The use of phonics knowledge is then used as a last prompt, "Look at the first letter" and perhaps "Sound it out."

While neuroscience tells us that this is not how we learn to read, this three-cueing model has been and continues to be a large part of balanced literacy reading instruction.

The three-cueing model relies on the following cues:

- Semantic (word meaning and sentence context)

- Syntax (grammatical structure)

- Graphophonic (letters and sounds)

The three-cueing model has been used in balanced literacy education for decades and falls under the belief that students read words first by analyzing meaning instead of reading the letters on the page. In contrast, attention to letters and sounds is not emphasized and is often considered the last and least reliable cue for reading words. Yet cognitive studies have shown that this approach does not teach children the critical skills to become proficient readers. Revealing functional MRI scans conducted in studies by neuroscientists indicated that the three-cueing model does not align with how our brains acquire reading skills (Brem S. et al., 2010). With this knowledge, revision of instructional practices that rely on language cues for reading new unknown words should be addressed in the classroom.

Why Does This Matter?

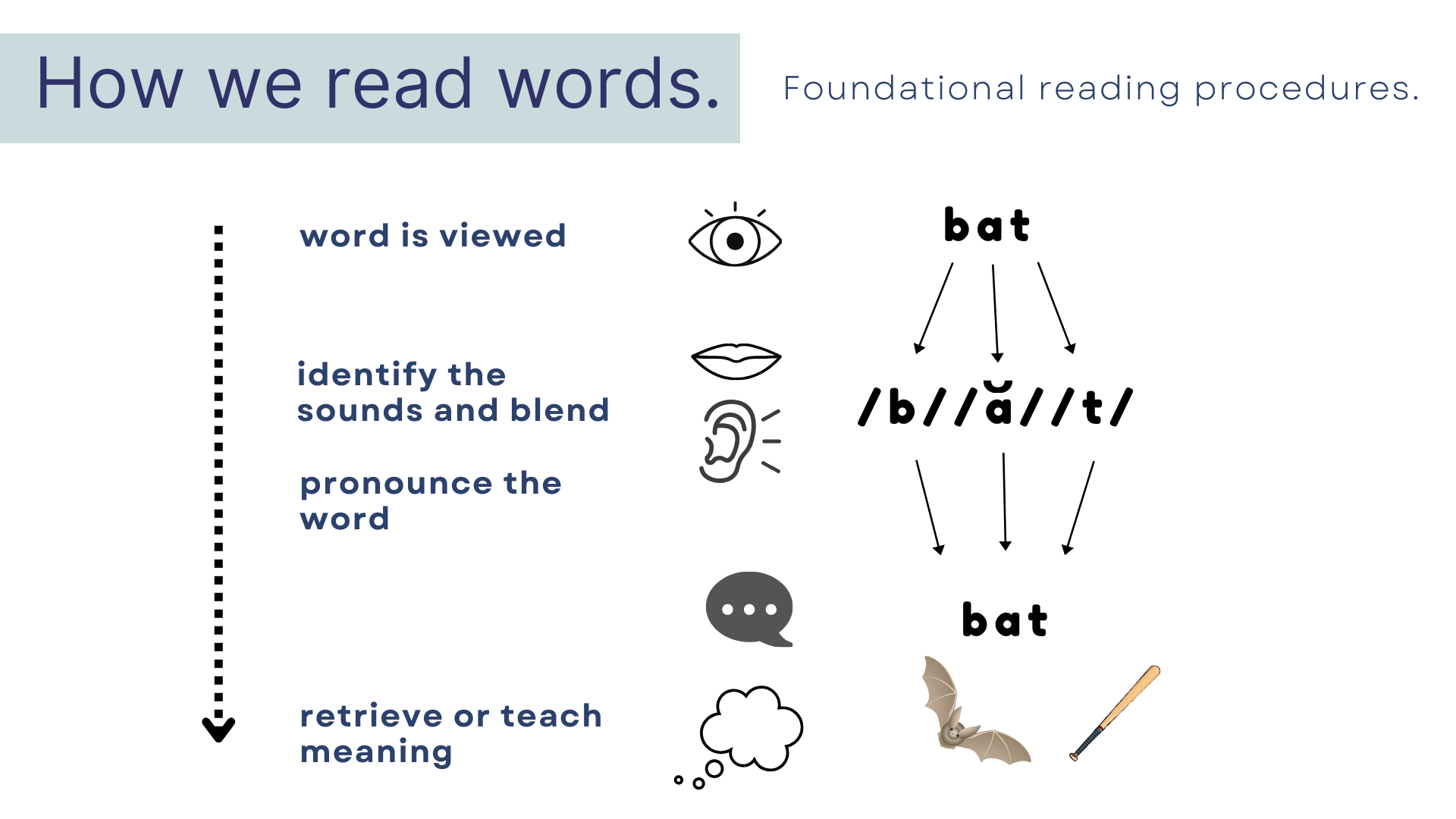

The belief that when reading, we rely on language or pictures to decipher a word is problematic because, as noted by researchers, reading is accomplished with letter-by-letter processing of the word (Raynor, Foorman, Perfetti, Pesetsky, & Seidenberg, 2001). Research has shown that we do not have a single location in the brain designated for reading. Instead, the brain relies on a network of systems, each meant for different things (language, vision, cognition), but together create a whole new circuitry so that we may read.

To automate this circuitry, we need to provide appropriate amounts of practice and correct repetition of skills to connect speech to print. The brain needs to make new neural pathways to convert our oral language to the written system of our language. This happens when we explicitly and systematically teach students the connection between the sounds in our language and the letters representing those sounds as we provide ample practice to apply their learning. Linking sounds to print should be the heavy lifting for beginning readers. There is no guessing involved in decoding a word.

The practice of linking sounds to print should be the heavy lifting for beginning readers. - Casey Harrison

Encouraging readers to use pictures or meaning cues to help them read a word is not how our brain learns to read. When we teach children to first look at meaning and pictures as a strategy to read words, it takes their eyes away from the text, essentially disrupting the importance of engaging the phonological processor and automating the phoneme-grapheme correspondence required to read proficiently.

As fluent readers, we may not realize that our brain does not skip over words or read print as whole words as our reading occurs in milliseconds. Eve-movement studies have shown that proficient readers do not skip words, use context to process words, or bypass phonics applications in establishing word recognition.

We do not bypass the phonological processor even in words that are somewhat irregular in our English print system. - Louisa Moats

Despite this information, a 2019 survey showed that 75% of elementary teachers used the three-cueing model when teaching reading in K-2 classrooms. Why? Most educators (myself included when I was in the classroom) are trained to teach this in the school system. While I haven't used the three-cueing model in almost two decades, I remember when this was part of every general education professional development I attended.

In addition, popular curriculums and assessments used in schools reinforce the idea that meaning first is the strategy for teaching students to read. We know there is a better way to teach students. Until educators and parents understand how to support students best and move past these ineffective strategies, it will continue to be a struggle for most students to achieve high levels of reading proficiency. Once these poor reading habits are established, they are challenging to break. I continue to have students come to the center who rely heavily on this habit of looking at pictures or the beginning sound and saying a word they think makes sense. Poor readers do this - and it is a hard habit to break once established as a "reading strategy."

What Do We Do Instead?

All readers must build a new reading circuit. Early foundational reading using a Structured Literacy approach addresses all components of literacy development noted by the National Reading Panel and provides students with sound foundational word reading skills. Students must be proficient in sound-letter associations to help them develop the skills needed for accurate and fluent reading. This includes letter-sound knowledge and spelling patterns. When students read or spell words based on the sound symbols explicitly taught, they engage in the orthographic mapping process, which is essential for reading and writing. This is done over time with a systematic scope and sequence that builds in difficulty. Understanding the relationship of the sounds in our language to the letter or letter representations helps students unlock the reading code.

In comparison, the three-cueing model is an ineffective instructional method and is misaligned with the science of reading. In addition, students taught the three-cueing method may encounter long-term reading difficulties (Moats, 2020) as it minimizes the importance of strong phonemic awareness and phonics. Instead, reading instruction should emphasize the explicit teaching of phoneme-grapheme correspondences within the English language and provide practice in reading and spelling with those letter-sound linkages.

Implications for Instruction

- Connect sounds to letters from the start. This instruction helps students link the sound that they hear with the letter representation for that sound. Over time, we increase our knowledge of phoneme-grapheme correspondence, moving from the most common letter representation to the least common.

- Have a clear scope and sequence. We want to understand that for our instructional practices, having a scope and sequence that introduces students to sounds first and then links or connects the spelling is key for the orthographic mapping process. We begin the mapping process by explicitly teaching the sound in connection to the letter representation and providing opportunities for children to work with these connections.

- Keep your eyes on the print! I tell my students this often, especially as they are beginning to read or if they are trying to break the habit of looking at pictures or guessing to read the words on the page.

- Keep kids from guessing at words. Explicitly teach decoding strategies focusing on sound-symbol relationships (phonics) and spelling applications to keep students from guessing.

- Use scaffolds when needed. Read more about decoding on the blog "Stuck on Decoding: 5 Ways to Scaffold Instruction" here.

Where DO Pictures Fit Into the Lesson?

One question that I am often asked is, "But what about picture clues?" If we think about how the brain unlocks the reading code, or our written system, we can shift how we use pictures to aid comprehension. Picture clues can be used to aid in meaning - but NOT for reading the words. We can look at the pictures after reading the words, but NOT as a strategy to figure out what a word is. Encouraging readers to use pictures to help them read a word is not how our brain learns to read.

*This post is speaking to the decoding/word recognition strands of learning to read. Both word recognition and linguistic comprehension are necessary to achieve the goal of reading. The use of pictures within the language strands is important - but here, when speaking to HOW children learn to read the words on the page, our focus should be on speech-to-print associations and decoding abilities to achieve automatic and accurate word recognition.

We all want our students to succeed and be literate. This means shifting how we teach beginning readers so they have the foundational skills and knowledge to decode and read the words on the page properly. As states are making changes in legislation and policies, I hope that they include proper support and training for our wonderful educators so that they can feel confident in applying these changes to their instructional approaches.

**This article is available as a PDF download in The Dyslexia Classroom Freebie Library - join here for freebies!

References

Dehaene, Stanislas. (2014). Reading in the Brain Revised and Extended: Response to Comments. Mind & Language. 29. 10.1111/mila.12053

Ehri, L. C. (2020). The science of learning to read words: A case for systematic phonics instruction. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(Suppl. 1), S45– S60.

Goodman, K. S. (1965). A linguistic study of cues and miscues. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED011482

Goodman, K. S. (1967). Reading: A psycholinguistic guessing game. Journal of the Reading Specialist, 6(4), 126-135.

Moats, L, & Tolman, C (2009). Excerpted from Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS): The Speech Sounds of English: Phonetics, Phonology, and Phoneme Awareness (Module 2). Boston: Sopris West.

National Reading Panel (2000). Teaching children to read, an evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction: Reports of the subgroups. Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/pubs/nrp/Documents/report.pdf

Perfetti, C., & Stafura, J. (2014). Word knowledge in a theory of reading comprehension. Scientific studies of Reading, 18(1), 22–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2013.827687

Rayner, K., Foorman, B., Perfetti, C.A., Pesetsky, D., & Seidenberg, M.S. (2002). How should reading be taught? Scientific American, 286(3), 84-91.

(4) (PDF) How Should Reading be Taught? (researchgate.net)

Rayner K., A. Pollatsek, J. Ashby and C. Clifton (2012) Psychology of reading. ( 2nd ed.). New York: Psychology Press.

Stanovich, K. E., Cunningham, A. E., & Feeman, D. J. (1984). Relation between early reading acquisition and word decoding with and without context: A longitudinal study of first-grade children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(4), 668–677.

Always learning,

Casey

This information is the intellectual property of @2016 The Dyslexia Classroom. Do not use or repurpose without expressed permission from The Dyslexia Classroom. Please give The Dyslexia Classroom an attribution if you choose to use, reference, or quote/paraphrase copyrighted materials. This includes but is not limited to blogs, social media, and resources.